“You never forget that day, as an immigrant, when you move to a different country,” Carlos Alvarado says. “There are certain things that you never forget.”

Alvarado, co-owner and principal broker of Alvarado Real Estate Group, came to Madison, Wis. on a foggy, rainy day in June 2002 to start a new life with his wife Sara, who was raised in Madison.

One of 11 kids, Alvarado was born in Puerto Vallarta, Mexico. As a kid, he sold popsicles at the beach to help support his family. After middle school, he began working at a restaurant, where he made his way up from a dishwasher to manager.

Not long after, he opened up his own restaurant and bar, putting years of entrepreneurial experience to the test. But when he moved to the United States, he desired a change of pace.

“I didn’t want to be in the restaurant [industry] anymore, because at that point, it was 13 years [of] being in that industry,” he explained. “Running a restaurant and managing a restaurant is a lot of work. It’s a lot of hours that you put into it.”

Shortly after immigrating to the United States, Alvarado enrolled in English classes at Madison Area Technical College (MATC) to sharpen his language skills, and would later go on to earn a degree in business from Edgewood College in 2018.

Within six months of moving to Madison, Alvarado began working as a bank teller on the south side of Madison, where most of his clients were Latino. And while he enjoyed his work as a teller, what he really wanted to be was a lender, but because of internal politics at his branch, Alvarado knew that this wouldn’t be possible there. Instead, he made the leap to join his wife who was already working in real estate at the time.

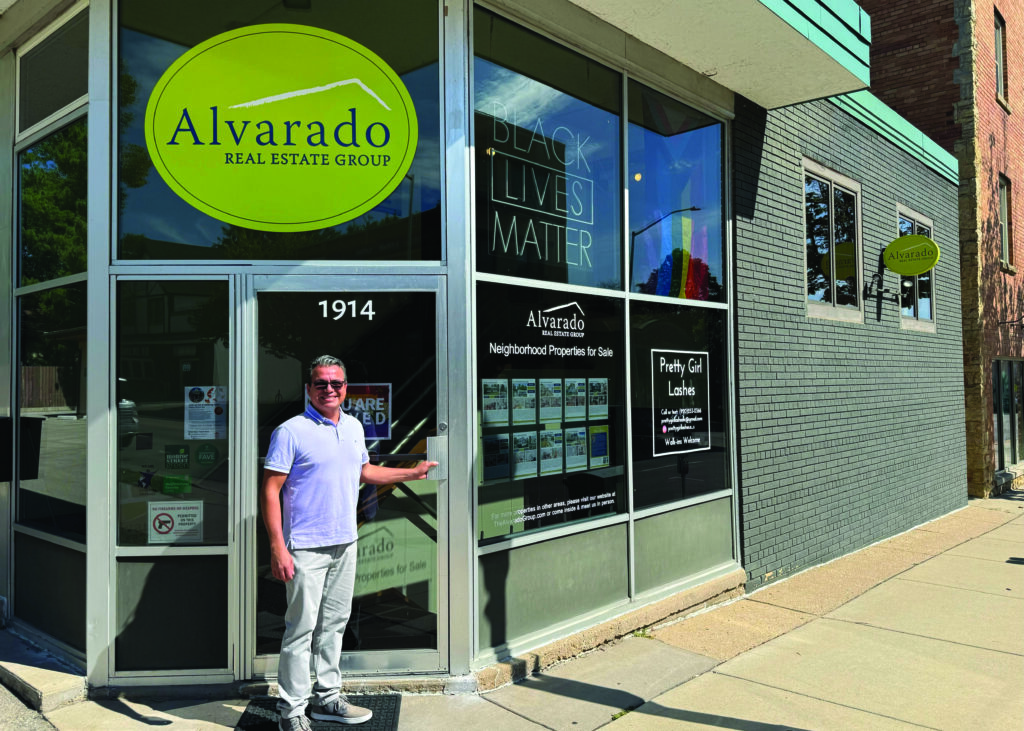

In 2008, with the knowledge that Alvarado learned at the bank about how to set up limited liability companies (LLCs), the husband and wife duo started Alvarado Real Estate Group. Renting a space on Williamson Street, the group started out as just the two of them and one admin person.

While others have encouraged him and Sara to expand their business over the years, Alvarado says its small size is one of the things that keeps it going. “[Running a company] is constant learning because you’re dealing with different personalities,” he explained. “Different people operate differently. Building a culture of collaboration is not easy.”

He continued: “Having your own [group] can give you the opportunity to have more impact on what you’re doing.”

Rather than quantity of brokers, Alvarado focuses on the quality of connections their group builds. “Real estate is about relationships for the most part,” he explained. “You’re building relationships all the time. We value that a lot.”

At its core, Alvarado Real Estate Group leads with “integrity and passion,” and puts supporting Madison’s BIPOC communities as a top priority.

As an immigrant himself, Alvardo is keenly aware of the disparities that immigrant and BIPOC Madisonians face when it comes to homeownership. According to the Dane County website, in 2020, 64% of white families in Dane County are homeowners, compared to 13% of Black families.

This disparity between white homeowners and homeowners of color is a gap that Alvarado Real Estate Group is actively trying to close in Madison. “One thing that we’re trying to do as a company is help minorities understand how you can actually build wealth through housing,” Alvarado says.

Compared to homeownership in his home country of Mexico, where a family typically passes one home down through generations, Alvarado explained that American homeownership is a means to build equity and advance financially.

“I learned here [the extent to which] people use the equity of their house to send their kids to college,” he says. Used as a form of generational wealth, owning—and potentially selling—a home in the United States “propels you to build equity and wealth over time.”

For people of color, the process of securing a first home is burdened by discriminatory policies based on race and immigration status. Alvarado used his own immigration story to emphasize how paths to homeownership are different when you’re a citizen or have support from American citizens.

“We moved here in ‘02, and in ‘03, because of Sara’s parents’ [help], we were able to buy a house,” he explained. “We didn’t have enough credit at that time, but her dad signed as a cosigner, and we were able to buy a house right away.”

“You don’t have that if you’re an immigrant—you don’t have the support of parents,” he emphasized. “You’re on your own.”

For undocumented Madisonians, the pathways to homeownership are “even fewer.” Alvarado explained that while there are currently some routes to homeownership, the monetary costs are much higher: While documented folks are able to access 0 to 3 percent down payment loans, the requirements for undocumented individuals can be as high as 10 percent.

“Trying to provide this information to the Latino [community] is super important,” he says. “Our intention is to be impactful about how we are providing information to everyone who is Black and brown who wants to own a house and build wealth through that.”

To put this goal of education into practice, Alvarado Real Estate participates in a city program called Own It — Building Black Wealth, which provides $18,000 in downpayment assistance to BIPOC community members to help them establish homeownership through monetary support and financial literacy classes.

To date, Alvarado Real Estate has contributed over $80,000 of its own revenue to Own It. “We try to bring together other realtors because we want everybody in the industry to participate,” Alvarado emphasized. “We understand that Black and brown people were [historically] denied loans and housing.”

Having been in Madison for over two decades, Alvarado has found his communities in places like the Latino Chamber of Commerce, on his kids’ soccer team, and as a member of the Madison-Tepa Sister City Project. To pay it forward, he wants to ensure that others—no matter their race or status—have a chance to make the city their home as much as he’s been able to.

“Building that community and support as an immigrant is important,” he says. “You feel like you can make this place your town.”