In Wisconsin, people of color are about half as likely than white people to own a business, and those businesses earn less on average.

Those are a few of the key takeaways from a study released earlier this year from University of Wisconsin Extension as part of The Wisconsin Economy series.

Tessa Conroy, an associate professor in the University of Wisconsin Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics and a co-author of the study, says people of color own about 50,000 businesses owned by people of color, which pay a combined billion dollars in payroll.

“The economic importance of these businesses is noteworthy,” Conroy says. “Businesses owned by people of color are growing much faster than the white, non-Hispanic segment of the population. Not only are they important, but they’re likely to become more important in the future.”

The growth has been most profound among Black-owned businesses; in 1997, there were fewer than 5,000; in 2012, there were more than 19,000.

In 2019, 42 percent of new entrepreneurs were people of color.

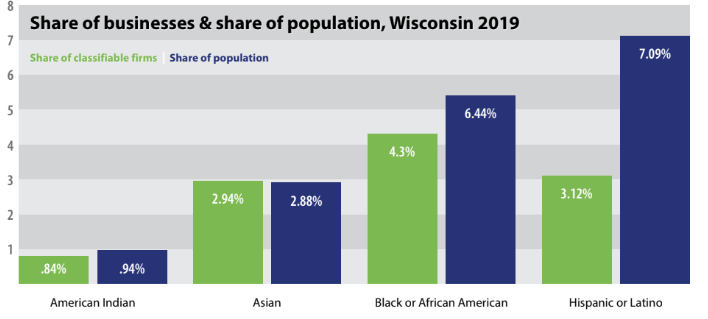

Those businesses still have a lot of catching up to do, though. While people of color – which, for purposes of this study, include Black, Indigenous, Asian and Latino populations – make up more than 19 percent of Wisconsin’s population, they make up less than 11 percent of business owners.

A major factor in that disparity is difficulty getting funding, Conroy says, noting that many POC-owned businesses are self-funded.

“Access to capital is always the top issue when we’re talking about entrepreneurship for anyone, and the challenge is even more acute for people of color,” she says. “Thinking about the availability of access to relatively small loans, or financing in small amounts, like rotating loan funds or incentive structures, is going to be really important for business owners of color.”

Nonemployer vs Employer

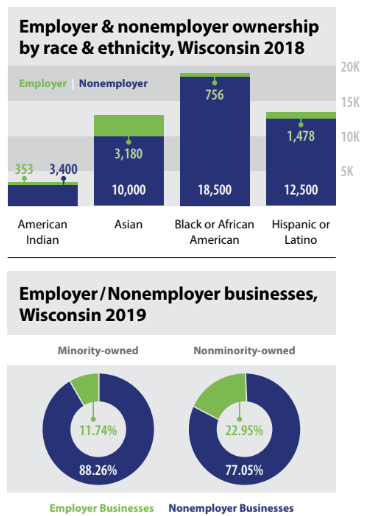

People of color are more likely than white people to own nonemployer businesses – meaning they don’t hire anyone other than themselves. That could take the form of someone being self-employed full time, or owning a business as a side job.

In fact, most businesses are of the nonemployer variety, regardless of who owns them. In Wisconsin, that works out to 77 percent of white-owned businesses, but 88 percent of minority-owned businesses. The disparity is most profound among Black-owned businesses, where less than four percent of businesses have employees, as of 2018. Asian-owned businesses actually outperform white-owned businesses in this measure; just over 24 percent of Asian-owned businesses are employer businesses.

Of all employer businesses, only 5.9 percent are owned by people of color. Nonemployer businesses still perform an important function in the economy.

“Non-employer businesses are really important seed beds for employer firms,” Conroy says. “There is evidence that 25 percent of businesses without paid employees intend to go on to hire employees.”

Intending to hire and actually being able to hire are different things, of course. One factor that might inhibit the ability to grow to the point of hiring is that people of color are more likely to start businesses in sectors that aren’t as lucrative.

“We see businesses owned by people of color tend to go into sectors that have relatively lower sales, and even within those sectors, businesses owned by people of color are earning less than their non-Hispanic white counterparts,” Conroy says. “Differences in access to education, capital, and broader systemic issues are going to play out in industry choice and business performance.”

Even among employer businesses, firms owned by people of color tend toward lower-revenue sectors; people of color business owners are overrepresented in accommodation &

food Services; retail trade; and health care & social assistance. These sectors, according to the study, can have lower capital requirements, making them more accessible to get into; however, that translates into lower upside and limited growth opportunities.

And even within those sectors, minority-owned businesses lag behind white-owned businesses. For example, employer firms in the health care and social assistance space owned by people of color average $1.5 million in sales, compared to $2.85 million for white-owned firms; in retail, it’s $2.5 million compared to $4.7 million.

Besides the choice of sector, location matters, as well, the study’s authors say. They note that businesses owned by people of color are more likely to be headquartered in diverse communities, where there are often fewer dollars to be spent.

“The lack of wealth in communities of color can contribute to a vicious cycle that stunts businesses owned by peoples of color and further curbs community development,” the study’s policy brief reads. “Driven by a history of spatial and social segregation, limited opportunities for diverse audiences, and disinvestment of public resources in communities of color, the local consumer base can experience greater financial difficulties and thereby have relatively low purchasing power. Weak purchasing power in these communities means constrained demand for local businesses, which are more likely to be owned by people of color.”

Higher sales and easier access to capital translates to higher employment, as well; in Wisconsin, white-owned employer firms employ 13.4 people on average. By contrast, Black-owned companies employ 11.2 people, Latino-owned firms employ 9.8, Asian-owned businesses employ 9.5, and Indigenous-owned businesses employ 5.6.

Looking forward

The study principally relies on pre-pandemic data, so long-term effects of the pandemic are yet to be measured. However, the study acknowledges disparities in the federal government’s response to the pandemic, and efforts to mitigate those disparities.

“Early on in the Paycheck Protection Program, the funds were largely distributed through banks, but people of color are less likely to have a relationship with a bank,” Conroy says. “Pivoting to community development financial institutions (CDFIs) helped better reach those communities.”

Many ethnic chambers of commerce operate or are affiliated with CDFIs and are therefore much more accessible to the members of those communities. (See pages xx-xx for more on a few of those organizations.)

The study does show, however, a “record-breaking” increase in entrepreneurial activity, as measured by The trick will be to harness that energy so new business growth is more equitable.

To that end, the study’s authors also produced a policy brief with recommendations for private sector companies and business development organizations as well as public sector agencies. Those recommendations include a wide range of ideas, including implementation of supply chain diversity programs, increased education and training on entrepreneurship, and increasing access to capital. All easier said than done.

The authors recommend expanding investment through CDFIs, which include community development banks, credit unions, loan funds and venture capital funds. They note that the State of Wisconsin issued $28 million in grants to nine CDFIs in its Diverse Business Investment Grant Program in 2021, which have in turn supported low capital small businesses. Additionally, traditional banks often invest in CDFIs, even when they have a difficult time investing in small businesses owned by people of color. Increased investing in these institutions could lead to lower disparities in business ownership, the study’s authors argue.

The study’s authors also posit that automated lending processes could lead to greater investment in POC-owned businesses by removing – or, at least, diminishing – bias in the application and approval process. They cite another study that found Paycheck Protection Program lending to Black-owned businesses was higher when processes were automated. However, they also acknowledged that the automated processes are still designed by humans, and as such could have biases built into them and actually deepen disparities in some cases.

The study’s policy brief also recommends creating more opportunities for businesses owned by people of color to become suppliers for larger companies and government agencies. They note that many large corporations and government agencies do intentionally seek proposals from diverse businesses, and do so by turning to lists of certified diverse or disadvantaged businesses. However, getting on those lists is not easy; certification can be an onerous and opaque process, especially for a solo entrepreneur or small business owner whose time is entirely dedicated to running the business day to day. Improvements in that process, as well as increased technical assistance to navigate it, are among the study’s recommendations.

The full study is available here, and the policy brief is available here.